Advanced Robot Manipulation and Admittance Control on the Franka Panda Robot Arm

Using robot manipulation, admittance control, computer vision, and machine learning to play word games with the Franka robot arm.

Link to this project’s Github

Team Members: Ananaya Agarwal, Graham Clifford, Ishani Narwankar, Abhishek Sankar, Srikanth Schelbert

Project Overview

The goal of this project was to use the Franka robot as a facilitator for a game of hangman. Our robot is able to setup a game of hangman (draw the dashes and hangman stand) as well as interact with the player (take word or letter guesses) before writing the player’s guesses on the board or adding to the hangman drawing.

In order to accomplish this project’s core goals, our team developed: a force control system combined with the use of april tags to regulate the pen’s distance from the board, an OCR system to gather and use information from the human player, and a hangman system to mediate the entire game.

Quickstart Guide - Running the Game on the Robot

- Install PaddlePaddle using

python -m pip install paddlepaddle-gpu -i https://pypi.tuna.tsinghua.edu.cn/simple - Install paddleocr using

pip install "paddleocr>=2.0.1" # Recommend to use version 2.0.1+ - Install Imutils using

pip install imutils - SSH into the student@station computer from the terminal after you are connected to the robot via ethernet cable.*

- On your browser open https://panda0.robot, unlock the robot, and activate FCI

- Once the robot is unlocked and has a blue light, use

ros2 launch drawing game_time.launch.xmlto open RVIZ and start the hangman game on the robot.

*you can only do this if you’re at the Northwestern University robotics lab, sorry

List of Nodes

-

Brain (Srikanth):

Interface with all other nodes and control their states. -

ImageModification (Abhishek):

Modify images for OCR using opencv. -

Paddle_Ocr (Abhishek):

Perform Optical Character Recognition (OCR) and publish character predictions. -

Hangman (Srikanth):

Plays the hangman game based on the OCR user input. -

Drawing (Graham):

Plan robot trajectories and calculate cartesian force at the end-effector, in the end-effector frame.Accept requests to plan trajectories for the Franka robot, and once planned send them to TrajectoryExecution to be executed. Additionally,calculate the estimated force at the end-effector, and publish it on a topic at 100hz.

-

TrajectoryExecution (Graham):

Execute trajectories planned for the Franka robot.Execute trajectories planned for the Franka robot at 10hz by publishing them one by one on the /panda_arm_controller/joint_trajectory topic. This is a stand in for the MoveIT execute trajectory action, since MoveIT doesn’t allow us to cancel action goals.

-

Kickstart (Ishani):

Kickstart handles setting up the board for the hangman game. This includes drawing lines on the board that signify where right and wrong hangman guesses should be drawn, and drawing the hangman noose. -

Tags (Ananya):

This node deals with the april tags and handles the ROS2 tf tree. When other nodes need to transform coordinates from one frame to another, they send a service call to this node for it to do it for them.This node knows where the frame of the whiteboard is, so it can compute transforms for coordinates on the whiteboard into coordinates in the space frame of the robot. This is necessary, since in order to plan a path for the robot, you need to first give it the coordinates in the robot’s space frame that you want the end-effector to travel to.

List of Launchfiles

-

game_time.launch.xml:

This launchfile launches the tags, kickstart, and brain nodes along with the ocr_game.launch.xml and drawing.launch.xml launch files.

-

ocr_game.launch.xml:

This launchfile launches the paddle_ocr, image_modification, and hangman nodes.

-

drawing.launch.xml:

This launchfile launches our RVIZ simulation and the april_tag.launch.xml.

-

april_tag.launch.xml:

This launchfile launches the camera configuration in RVIZ along with the pointcloud information. It also launches the tags node.

Overall System Architecture

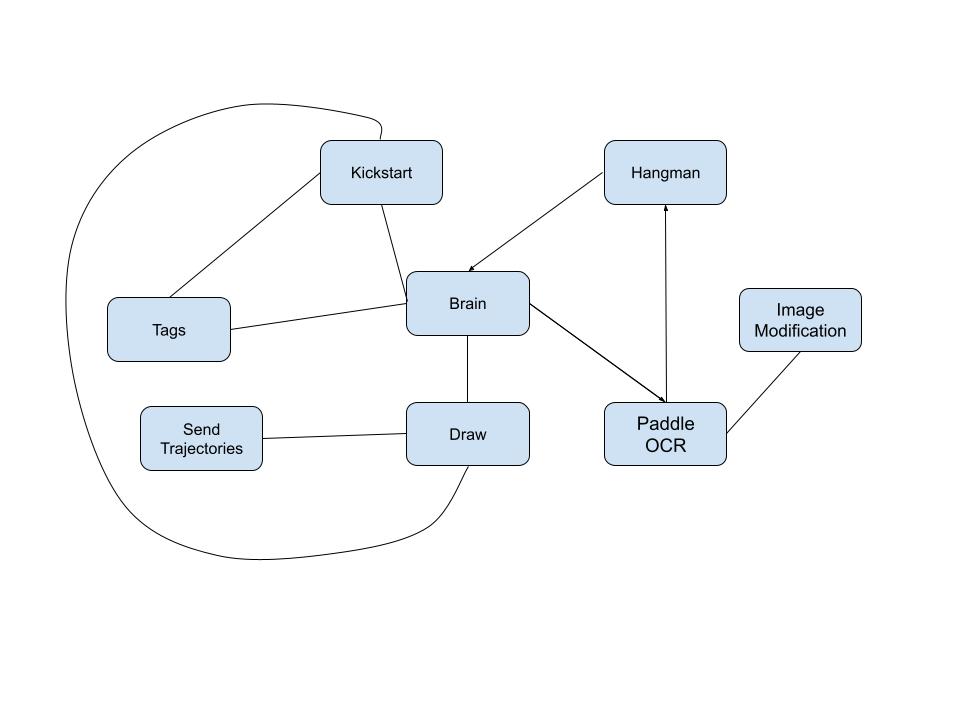

The following diagram illustrates the overall system design and showcases how different nodes interact with eachother in order to accomplish the goals of our project.

Admittance Control

This was my main contribution to the project. I almost spent as much time implementing admittance control as I spent figuring out how not to implement admittance control.

How Not to Calculate the Force at the End-Effector

I started with a goal: to find the force at the end-effector, in the end-effector’s frame, in the cartesian (xyz) directions.

First I tried to use libfranka, which is the Franka robot’s C++ library, because it computes these forces itself to begin with. However, since the rest of our nodes and project relied on the Franka robot’s ROS2 launchfiles, I could not take this route. The reason is that in order to access the force at the end-effector through libfranka, I would need to create an instance of the Robot class. There cannot be two instances of the Robot class at the same time, and the Franka’s ROS2 launchfiles create an instance of the Robot class that I did not have access to.

Next, I tried calculating the force at the end-effector myself using equation 5.26 from the Modern Robotics textbook by Kevin Lynch:

\[\tau = J^T(\theta) \mathcal{F}\]In order to get the force at the end-effector, we have to solve this equation for the wrench \(\mathcal{F}\), so we end up with this equation:

\[\mathcal{F} = J^{-T}(\theta) \tau\]And since the Franka arm has 7 degrees of freedom (DOF), the Jacobian matrix J is overloaded and is a 6x7 matrix when not at a singularity and so we have to take the pseudo inverse:

\[\mathcal{F} = J^{\dagger}(\theta) \tau\]In my head, this should work great. In practice, it did not work great. In the perspective of the space frame, I ended up with non-zero force in the x, y, and z directions due to the weight of the robot arm itself.

I delved deeper into the math here to try and make it work, but I came to a disappointing conclusion: I didn’t have enough information to do the math right. I wanted to use the GravityForces function from the ModernRobotics python library to calculate the expected torque in all of the Franka’s joints due to the force of gravity:

Input:

thetalist: n-vector of joint variables θ.

g: Gravity vector g.

Mlist: List of link frames {i} relative to {i − 1} at the home position.

Glist: Spatial inertia matrices Gi of the links.

Slist: Screw axes Si of the joints in a space frame.

Output:

grav: The joint forces/torques required to balance gravity at θ.

However I was missing the Glist variable, and there wasn’t really a way to get it.

At this point I gave up on performing the math myself, however I soon thought of a simpler way to calculate the force at the end-effector.

How to Calculate the Force at the End-Effector

Here’s what I came up with:

- Since panda_joint6 (the sixth joint) of the Franka robot only ever holds up panda_link7 and the gripper itself.

- Because this is true, that means that when panda_joint6 is in a specific position, not touching anything, I can calculate the amount of torque in panda_joint6 due to the weight of panda_link7 and the gripper.

- Then, this means that if I always write letters on the whiteboard with panda_joint6 in a specific position, I will always know how much torque in panda_joint6 is due to gravity, and how much of the torque is due to external forces.

- This will allow us to do admittance control!

After performing some intial tests, this worked great. Soon I was able to increase the accuracy of this measurement after I discovered that Franka provides the exact location of the center of mass of the gripper and the mass of the gripper. Using this information, I can calculate the expected torque in panda_joint6 due to the mass of the gripper at all positions of panda_joint6.

How to Bypass MoveIt’s Execute Trajectory Action Server

My definition of Admittance Control is using the external forces on a robot as the input, and providing the position of the robot as the output.

Now that I can calculate the force at the end-effector of the Franka robot in real time using python, my first goal was to be able to have the robot arm go and touch the whiteboard, and when it makes contact with enough force I wanted it to stop moving. This proved challenging. The way our group was moving the robot arm was we would have the MoveIt motion planner plan a path, and then we would have the MoveIt execute trajectory action execute it. Theoretically, you should be able to cancel action goals in ROS2 Iron, but I wasn’t able to perform this for some reason despite copying code from the official ROS github.

Instead of this, I decided to write a node to take place of the MoveIt execute trajectory action.

To accomplish this, first I inspected the RobotTrajectory message generated by the MoveIt motion planner. I noticed that this message is essentially just a JointTrajectory message, inside which there is a list of JointTrajectoryPoint messages. JointTrajectoryPoint messages consist of what joint angles, joint velocities, and joint accelerations for the robot arm, and additionally they contain a parameter called time_from_start. This parameter tells the MoveIt execute trajectory action server precisely when the robot should achieve the joint angles, velocities, and accelerations define in the same message.

time_frome_start has units of nanoseconds, and typically in a RobotTrajectory message generated by the MoveIt motion planner the list of JointTrajectoryPoints have time_from_start parameters spaces 100ms apart, or 100000000ns apart.

I wanted to execute each of these JointTrajectoryPoints one by one, however the only way to execute trajectories manually is to publish a JointTrajectory message onto the /panda_arm_controller/joint_trajectory topic. To accomplish this, I reformatted the RobotTrajectory generated by the MoveIt motion planner into a list of JointTrajectories, each containing one JointTrajectoryPoint. This is opposite to before, where we had one JointTrajectory containing a list of JointTrajectoryPoints.

I wrote the ROS2 node and included a timer with a frequency of 10Hz. It also provides a service called /joint_trajectories, which allows other nodes to queue joint_trajectories to be executed. This service creates a Future object, and only returns the Future object once the requested trajectory has been fully executed or canceled. The node will publish JointTrajectory messages that it receives via service calls to the /joint_trajectories service one by one, every 0.1 seconds, until there are no more JointTrajectory messages left.

Putting Everything Together, Performing Admittance Control

Now we have all the pieces in place, we can perform admittance control. Let’s assume the robot is currently holding a whiteboard marker, and it’s currently slowly moving towards the whiteboard. Ignore how we got here.

After the whiteboard marker the robot arm is holding has collided with the whiteboard, the send_trajectory.py node will issue a replan request to the tags.py node. This request is telling tags.py that the robot arm has collided with the whiteboard, and that tags needs to plan a to finish the trajectory using the current position of the end-effector as the start point.

After the replan request is complete, the send_trajectory.py node will enter into a PID loop using the force at the end-effector as an input, and the angle of panda_joint6 as an output. The reason the the output of the PID loop is panda_joint6 is that when I was implementing this I was pressed for time. It’s not the best solution, and it causes the robot to draw curved lines.

In the near future, I will update the PID loop so that the position of the end-effector with respect to the whiteboard is the output. This output can then be used to calculate a new point to continue drawing the current letter on the whiteboard from, and then this new point is used to perform inverse kinematics. The joint angles received from the inverse kinematics service are used to update the JointTrajectory messages being published on the fly. Pretty cool! As long as it’s fast enough, I believe that it will be more accurate than what I have currently implemented.

Future Work

Although our team redesigned a spring force control adapter for the Franka gripper for our fallback goal, we quickly outgrew the need for it as we began trying to implement force control. However, our project could still be significantly improved on the force control side of things. By the demo day, our team had achieved using force control to draw characters on the board but could have improved the quality of writing with more time to tune the force control parameters.

Along with improving force control, our team envisioned incorporating an extra part of the game where the robot picks up different colored pens depending on whether the player’s guess is right or wrong. Due to the amount of people on our team, we actually designed and manufactured the pen stand and began writing the code to implement this part of our project. We had finalized our gripper code and had begun calibrating the robot to our april tag on the pen stand. We unfortunately ran out of time incorporating this into our final gameplay.

Our final stretch goal that we would love to improve our project with is changing the board position between the player’s turns. Due to our use of april tags and force control this could have been implemented with additional time to properly calibrate the camera’s exact position with respect to the board and robot.

Demonstration Videos

The following video showcases a full runthrough of our project. In it, we demonstrate the robot’s ability to calibrate and determine the position of the board, run through the game setup sequence while using force control, and interact with the player and receive both single letter and full word guesses.